This discusses how modularity helps to make complexity in software system manageable.

The most import measure of Complexity is the financial cost associated with software maintenance: i.e., the cost required to change a System.

A number of independent studies concur that software maintenance accounts for ~80% of the total lifetime cost of a software system: e.g., Erlikh, L. (2000) determined that 80% of software costs are concerned with evolution of the software.

These costs typically break down into the following activities:

To provide a financial context, let’s apply this breakdown to some example project costs:

Given the increasing sophistication of modern software solutions, these figures almost certainly underestimate the total lifetime costs.

Here we are of course simply restating DARPA’s observation.

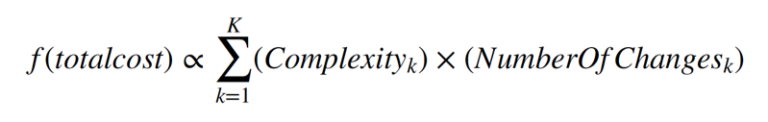

For an Organization with K Systems, the change related costs per period of time can be expressed as:

where

To minimize change costs we simply need to minimize this expression.

If we ignore the role of Modularity, what other approaches are available for managing Complexity? Possible approaches to reducing Operational costs (the proxy for Complexity) might include:

Traditional IT strategies usually include one or more elements of the above.

A no change strategy results in extremely fragile operational environments. When the inevitable unplanned environmental change occurs (i.e., resource failure or operational error), this event is much more likely to have a catastrophic effect: i.e., a Black Swan event.

Real world organizations, even those with static business models that require no new functionality, must still respond to security patches, fixes and accommodate environmentally forced changes.

Sometimes an approach to reduce complexity is to try and reduce the number of applications by consolidating functionality.

However, if we consider Glass’s law we can immediately see a problem. Consider three business services each composed of 4 functions, 3 of which are the same for each System;

System A (a,b,c,x), System B (a,b,c,y), System C (a,b,c,z)

The Complexity estimate for these three systems would then be:

System A (43.11) + System B (43.11) + System C (43.11) =~ 224

Whereas the equivalent consolidated System D (a,b,c,x,y,z) will have a complexity measure of 63.11 = 263.

In this example, while Operational Complexity decreases – managing 1 application instead of 3, Code Complexity (the much larger issue), remains essentially unchanged. The degree of functional overlap between Systems being consolidated may be greater than 75%, or one may argue that the exponential 3.11 is too high for your organization; however, the argument concerning the ineffectiveness of functional consolidation in reducing complexity still stands.

Also, note that Operational flexibility and resilience are reduced as the whole User population is now dependent upon the one monolithic application.

So this is perhaps not the desired outcome for a multi-million dollar application consolidation program?

Here we are simply handing over our Complexity problem to a 3rd party.

The 3rd party typically achieves a lower cost by preserving the status-quo and using cheaper engineering resources to implement change requests rather than re-engineering the applications to reduce complexity. As changes remain challenging the 3rd Party is incentivized to minimize these, and charge a premium for exceptions not covered in the contract.

These approaches move the Complexity problem from a physical platform to a virtual platform.

Virtualization has no-effect on application complexity and increases infrastructure complexity. Investment in Virtualization or Container strategies should only be justified on infrastructure costs savings through increased resource utilization. These cost saving calculations should also account for potentially significant increases in infrastructure complexity, which in turn can lead to increased Service outages.

The same argument applies to 3rd Party Cloud providers; moving an Application to a third party Cloud environment has no effect on the Application’s internal complexity. However, 3rd Party Cloud providers do shield you from the infrastructure complexity, although of course there costs associated with using them.

Finally, rather than trying to maintain an existing monolithic code base, this approach is to wholesale rewrite the application each time major changes are required.

This may be a valid strategy for small consumer apps or start-ups, but is increasingly not valid for sophisticated and long living business-critical applications and systems (e.g., Telco, Financial Services, or Industry 4.0) that require ongoing incremental enhancements to a complex inter-related ecosystem of Services.

Ironically, the more modular the overall software ecosystem, the simpler it becomes to rapidly rip-n-replace individual Modules.

If traditional strategies fail to address the fundamental problem of Application complexity, what about current application trends?

Do these help?

A limited modularity strategy may be pursued via the adoption of REST based Microservices.

By ’limited’ we mean that large applications are broken down into a set of smaller deployable Services that communicate with each other via REST. However, in most cases, the internal implementation of each Microservice remains non-Modular. This is also an example of Forced Conformity / Reduced Diversity as all applications must use HTTP/REST to communicate.

Contrary to the consolidation example, we now break the Systems System A (a,b,c,x), System B (a,b,c,y), System C (a,b,c,z) into the Microservices µa, µb, µc, µx, µy, µz.

These can then be re-combined into Composite Systems A(µa, µb, µc, µx), B(µa, µb, µc, µy), C(µa, µb, µc, µz).

As discussed in Qualitative Measures, while code complexity is significantly reduced we have created Orchestration complexity as a by-product: see Complexity & Hierarchy.

REST/Container centric Microservice strategies generally lack standards-based mechanisms to manage this Orchestration complexity, and so the problem is exposed to Operations.

The Twelve-Factor methodology is a variant of the REST/Microservices trend.

The Twelve-Factor methodology encourages:

Like Microservices, the Twelve-Factor methodology is applicable to any application written in any programming language. However, just like Microservices, to achieve this language agnostic position, the Twelve-Factor App needs to specify a number of application design constraints which may or may not be acceptable.

While mentioning the benefits of modularity and dependency management the Twelve-Factor methodology is vague about how this should be achieved. Both heavyweight monoliths or highly modular Composite Systems like our enRoute Microservices example may be crafted to be “Twelve-Factor” compliant.

While the Twelve-Factor methodology does not address Application Complexity, like REST-based Microservices it may be one of a number of useful design patterns used within the context of a more all-encompassing Modularity strategy.

In a Serverless environment, developers create units of Application logic that are instantiated in third-party Function-as-a-Service (FaaS) compute offerings: i.e., databases, search indexes, queues, SMS messaging, email delivery, etc. While conceptually very similar to compute Grid offerings that were available over a decade ago the recent Serverless movement prefers to reference AWS Lambda as the inspiration.

FaaS is an example of a Hide Complexity strategy, as the developer’s concern is only the Application logic, with all software infrastructure provided as third-party Services.

Stated benefits of Serverless include:

Also, as FaaS is charged based on usage rather than pre-provisioned capacity, significant cost-savings (~90%) can be achieved relative to an equivalent number of provisioned cloud VM’s hosting the same services.

While the FaaS User is decoupled from the underlying runtime infrastructure provider; they are, of course, coupled to the Serverless framework via deployment descriptors: the runnable code needing an associated deployment descriptor (YAML/JSON) that describes all environmental dependencies and lifecycle for that framework. So while as a Developer or User you are not concerned about Orchestration or infrastructure complexity; these problems still exist for the FaaS Service Provider, and will likely bleed into the pricing structure downstream.

If your Application problem maps to a Serverless model; if resource usage is unpredictable and bursty; and if you are happy to hand off the required software infrastructure services to a third party, then the FaaS pricing model is attractive.

However, the following facts should also be remembered:

Finally, while a number of open source projects exist, there are currently no industry standards for defining dependencies or lifecycles; hence the User is coupled to a FaaS implementation, and a significant amount of Complexity is hidden within the FaaS Service which is managed by the FaaS provider in the traditional manner.

Proponents of REST-based Microservices, Twelve-Factor and Serverless also tend to be Polyglot advocates: arguing that runtime services can be written by developers using their favorite language of choice.

However, this is inconsistent with Forced Conformity / Reduced Diversity. From a maintenance perspective, an overly indulgent Polyglot strategy is a significant Organizational problem. Consider a Microservice processing pipeline consisting of Python, Go, Rust, C++ and Haskell Service components. Maintenance of this Service requires the Organization either:

It is also worth noting that the TIOBE Index for January 2018 yet again places Java as the industries leading programming language, a position broadly held since 2003: this is perhaps an indication that senior management in Organizations understand that unnecessary language diversity (unnecessary Complexity) is an excellent mechanism for generating explosive levels of runtime complexity (see CISQ Technical Debt Calculation), and of course future recruiting issues: i.e. vacancy for a developer – must have 5 years experience in all of the following – Python, Go, Rust, C++ and Haskell.

A common response to uncontrolled Operational Complexity is DevOps.

In the DevOps model, the Development teams are made responsible for all aspects of their Application; from code development to Production. The argument is that Developers can ‘deal’ with the Operational complexity; and direct access to Production Systems – without Operational barriers – allows the developer to deploy code, and recover from the errors caused by the deployment, more rapidly.

However, the DevOps model results in tight coupling between Development teams and the Operational Services for which they are now responsible. This tight-coupling introduces systemic Operational Risk: talented members of a Development team are more likely to leave the company, and in a DevOps centric environment, this immediately translates to an Operational risk to the business: The Wetware Crisis: the Dead Sea effect.

Complexity is a critical business problem. Complexity cannot be ignored, cannot be consolidated away, hidden by a third Party Cloud, or an outsource contract. Directly or indirectly the costs associated with Complexity will always re-emerge.

A Modularity first strategy is the only way that Complexity can be addressed, and highly maintainable, economically sustainable software systems delivered.

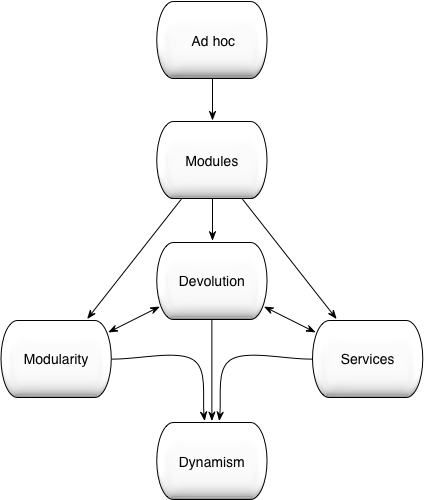

As explained in the Agility and Modularity: Two Sides of the Same Coin OSGi white paper, senior management are familiar with the concepts of modularity and dependencies when in the context of Organizational management structures. Recognizing this, the Modularity Maturity Model was proposed by Dr. Graham Charters at the OSGi Community Event in 2011, as a way of helping management assess how far down the modularity path their organization or project is. It is named after the Capability Maturity Model, which allows organizations or projects to measure their improvements on a software development process.

Note that the following terminology is implementation agnostic, in that, it can be applied to any modularity model. The following is also intended as a guide rather than being prescriptive.

No formal modularity exists. Dependencies are unknown. Applications have no, or limited, structure. Agile processes are likely to fail as application code bases are monolithic and highly coupled. Testing is challenging as changes propagate unchecked, causing unintentional side effects. Governance and change management are costly and acknowledged to be high-level operational risks.

Named modules are used with explicit versioning. Dependencies are expressed in terms of module identity (including version). Maven, Ivy, and RPM are examples of modularity solutions where dependencies are managed by versioned identities. Artifact repositories are used; however, their value is compromised as the artifacts are not self-describing. Agile processes are possible and do deliver some business benefit. However, the ability to realize Continuous Integration (CI) is limited by ill-defined dependencies. Governance and change management are not addressed. Testing is still failure-prone. Indeed, the testing process is now the dominant bottleneck in the agile release process. Governance and change management remain costly and continue to be high-level operational risks.

Module dependencies are now expressed via contracts (i.e., capabilities and requirements). Dependency resolution becomes the basis of software construction. Dependencies are semantically versioned, enabling the impact of change to be communicated. By enforcing strong isolation and defining dependencies in terms of capabilities and requirements, modularity enables many small development teams to efficiently work independently and in parallel. The efficiency of Scrum and Kanban management processes correspondingly increases. Sprints are now associated with one or more well-defined structural entities; i.e., the development or refactoring of OSGi bundles. Semantic versioning enables the impact of refactoring to be contained and efficiently communicated across team boundaries. Via strong modularity and isolation, parallel teams can safely sprint on different structural areas of the same application. Strong isolation and semantic versioning enable efficient/robust unit testing. Governance and change management are now demonstrably much lower operational risks.

Services-based collaboration hides the construction details of services from the users of those services, so allowing clients to be decoupled from the implementations of the providers. Services lay the foundation for runtime loose coupling. The dynamic find and bind behaviors in the OSGi service model directly enable loose coupling by enabling the dynamic formation of composite applications. All local and distributed service dependencies are automatically managed. The change of perspective from code to OSGi μServices increases developer and business agility yet further: new business systems being rapidly composed from the appropriate set of pre-existing OSGi μServices.

Artifact ownership is devolved to modularity-aware repositories, which encourage collaboration and enable governance. Assets may be selected on their stated capabilities. Advantages include:

As software artifacts are described in terms of a coherent set of requirements and capabilities, developers can communicate changes (breaking and non-breaking) to third parties through the use of semantic versioning. Devolution allows development teams to rapidly find third-party artifacts that meet their requirements. From a business perspective, devolution enables significant flexibility with respect to how artifacts are created, allowing distributed parties to interact in a more effective and efficient manner. Artifacts may be produced by other teams within the same organization or consumed from external third parties. The Devolution stage promotes code re-use and increases the effectiveness of offshoring/nearshoring or the use of third-party, OSS or crowd-sourced software components. This, in turn, directly leads to significant and sustained reductions in operational cost.

Dynamism is the culmination of the organization’s Modularity journey: this built upon Modularity, Services, and Devolution.

Each Organization’s modularization migration strategy (i.e., the route to traverse these modularity levels) will be dictated by which characteristics are of most immediate business value to the Organization. Most Organizations have moved from the initial Ad-Hoc phase to Modules. Services, in the guise of ‘Microservices’ are currently popular, however, few Organizations have implemented true Modularity or Devolution. Organizations that value a high degree of Agility and/or Adaptive Automation will wish to reach the Dynamism endpoint as soon as possible.

Complexity is the primary issue that affects the economic sustainability of software systems. As detailed in Design Rules, Volume 1 The Power of Modularity, modularity makes complexity manageable. Therefore a coherent strategy for modularity, based on open industry standards, must be our start point.

This modularity first strategy must define how to describe dependencies and lifecycles for all entities, at all structural layers, of each Composite System: from the fine-grained artifacts created by component developers to the distributed Composite System run by Operations; enabling all layers of the runtime environment to be automatically Assembled/Orchestrated.

It is important to note that such a modularity first strategy does not exclude REST-based Microservices, use of Cloud, a Twelve-Factor App approach, or the use of Function-as-a-Service (FaaS). Rather a modularity first strategy is an enabler for maintainable versions of all of the these; while also ensuring that these design decisions can be changed at a later point in time in response to changing Business requirements.

Today, OSGi/Java is the only modularity/language combination powerful enough to address the Complexity Crisis and the longevity challenge described by DARPA. The OSGi Working Group is also exploring the generalization of the OSGi Dependency Management and Service Registry concepts, to bring these benefits to other popular languages.